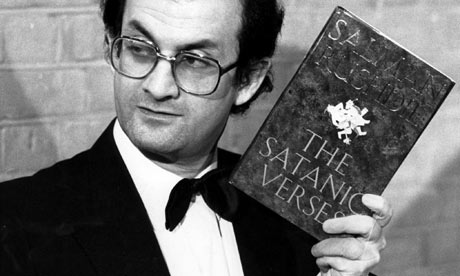

A couple of years ago, I had the pleasure to take part in an event at the University of Warwick's annual Warwick Student Arts Festival in which the goal was to take a book and convince the audience that they should read it – the winner being voted on by the participants of the competition. While most of the books have drifted into memory now, I remember snatching second place to a friend of mine who was attempting to sell Conan the Barbarian, by Robert E. Howard. What I do remember vividly are the reasons for choosing the book I attempted to sell, which was 'The Satanic Verses' by Salman Rushdie. Furthermore, I found the book incredibly difficult to sell on the basis that many people were put off by the controversy surrounding it.

The book, hopefully, is familiar, but unfortunately the numbers that have read it are dwarfed by those who are aware of the huge controversy that surrounded the book, leading to the Ayatollah Khomeini's issuing of a fatwa for the death of Rushdie, and his subsequent disapearance from public life. The issue surrounded Rushdie's portrayal of a character in the book, who resembled Mohammed, as a secular and base character, quite apart from the privileges bestowed upon him by Islam as a whole. It is far from the only controversy that Rushdie has courted, the second most memorable being his portrayal of Indira Gandhi in his (to my mind) opus, Midnight's Children.

My choice of book was guided largely by my belief that many who had criticised and discussed the book, in much the same way as the discussion that surrounded the infamous Danish cartoons of Mohammed, had not read the book, much less have a grip upon the substantive ideas that it presented.

I will admit to being a huge fan of magic realism, from Marquez and Llosa through to Bulgakov and Kundera, and believe that Rushdie is a master of the form. His novel inverts the usual relationship of the spiritual and magical to the mundane, with key religious events approached with a secular, human sobriety, and everyday life examined through a lens seemingly smothered in fairy dust. Indeed, the twist that facilitates the interlocking narratives of the Satanic Verses is nothing if not an entirely human foible, drawing attention to the strange mix of lofty ambition and day to day struggle that puts humans somewhere between angels and insects.

This, quite apart from the offence caused, is a topic of great pertinence at the moment, with the Christian equivalents perhaps being portrayed in the 2005 film Son of Man, that depicted Jesus as a political figure, and the recent novel The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ by Phillip Pullman, that demonstrated the fundamental weaknesses of whatever is human. However, it should not be the existence of such works that provokes controversy – religions have never had a problem finding suitable heretics – but rather the content of the ideas themselves. The debate surrounding the Satanic Verses seemed to contain little debate as to the ideas, but rather the political issue of the fatwa, when the opposite should have been the case.

While The Satanic Verses is hardly a textbook on Islamic thought, it is most definitely worth a read as a way of approaching the debate concerning the representation of Mohammed and Allah in Islam – a debate which goes back to the Ottoman Empire and before (for another fantastic book on the subject, set in Istanbul, check out My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk). Indeed, not reading it because of the controversy is doing the spirit of public debate a disservice. Above that, though, it is a masterful piece of fiction, and shouldn't that be reason enough?

Wednesday, 13 October 2010

Saturday, 2 October 2010

Acceptable Language and the Expulsion of the Roma

I realise that this topic involves taking some risks – particularly given my potential academic future in the study of politics, but the following question came up when I was chatting to a friend about the expulsion of the Roma from France, in all its repugnant glory:

“Is the expulsion of the Roma comparable to the Holocaust?”

Bang. There we go. If you're still reading, then it means you probably have a fairly strong stomach, and this debate is going to need it. Quite apart from the collective sense of guilt that is often felt, particularly in Germany, concerning the Holocaust, my argument will be that it is possible to compare the two. Furthermore, my claim is that not comparing the two due to the unparalleled extent of the Holocaust may be doing the Roma expulsion a disservice, if not encouraging the escalation of the othering practices used against them.

For those relatively familiar with the more language-based and critical political theories surrounding the issue, it should be apparent while there isn't necessarily an ethical imperative to not discuss this comparison (in fact I will argue the opposite), acceptable language defines it as something that is not to be discussed, at least explicitly. This is based in the linking of specific emotions to the terms 'Holocaust' or 'genocide'.

However, on the assumption that the connotations of verbal acts are negotiated and developed over time, this link does not stand ex-ante (before the utterance), but has a history of its own. In the case of the Holocaust, the very real link between the word holocaust and a particular historical circumstance – the genocide of the Jews by the Nazi government in Germany – demonstrates this. In particular, it is interesting to note that up until this point I have not expanded my particular definition of Holocaust, but the capital letter 'H' that denotes a proper noun rather than its abstract is likely to have already made that link in your mind. While there are many debates around this, this short piece takes the above assumption as a given.

So somewhere along the line, the undeniable link between the term Holocaust and emotions of guilt, anger or fear have been forged and submitted to the public consciousness, and while the occurrence is undeniable, it also stands that it is one of many possible definitions that may have occurred. It is also worth noting that there is a great deal of historical specificity to the term Holocaust, and herein lies the problem.

For many, if not most people, the term Holocaaust denotes the genocide committed against the Jews. My assertion here though, is that the Holocaust thus mentioned can only be discussed in light of the many processes that led up to the final event, including the legislation etc. that was passed in order to facilitate it. One of these measures included the expulsion of Jews from particular areas of public or private life, which is where the comparison with the expulsion of the Roma comes in.

Again, it is not my aim to compare the Holocaust, fully drawn out, with the expulsion of the Roma. But in comparing the processes that led up to it, it is far more likely that we are able to acknowledge the danger of certain paths without proclaiming their imminent eventuality. The expulsion of the Roma, repugnant as it is, has not, and does not need, to lead to another Holocaust, purely by virtue of the lessons we learnt from that event – itself a form of comparison. If we are not to speak of the Holocaust with reference to current events, what lessons have we learnt? The construction of acceptable language to shut down discussion in this light, I believe, is something that constricts public debate in a way that cannot be positive. Furthermore, it acts against the moral imperative that we learn from our mistakes in order to avoid making them again.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)